Free 2D & 3D Scientific Graphing Calculator

Scientific Graphing Suite

System ReadyConfiguration

Ripple Saddle Waves Peak

Syntax Guide

- Powers:

x^2 - Trig:

sin(),cos(),tan() - Log:

log(x),sqrt(x) - Constants:

pi,e

Calculation Log

| Timestamp | Mode | Expression | Range |

|---|

Found our Free 2D & 3D Scientific Graphing Calculator useful? Bookmark and share it.

Article Index

- Introduction: The Dimensional Shift in Computational Tools

- Part I: The Pedagogical Revolution in STEM Education

- Part II: The Artistic Frontier and Algorithmic Design

- Part III: Engineering, Architecture, and Professional Utility

- Part IV: Hardware Ecosystem and Technical Capabilities

- Part V: Augmented Reality (AR) - Merging Worlds

- Comparative Analysis of Technical Capabilities

- Detailed Case Study: The Aizawa Attractor

- Conclusion

TL;DR

The evolution of 3D graphing calculators has shifted STEM education and professional design from flat, static projections to dynamic, immersive experiences. Tools like GeoGebra and Desmos have revolutionized how students visualize multivariable calculus, while programmable handheld units from TI and Casio now support Python for advanced physics simulations. Beyond the classroom, these calculators serve as engines for algorithmic art (e.g., strange attractors) and accessible CAD platforms for architectural prototyping and 3D printing. This article explores the technical capabilities, artistic applications, and pedagogical impacts of modern 3D graphing technology.

Introduction: The Dimensional Shift in Computational Tools

The history of mathematical pedagogy and professional computation has been inexorably tied to the limitations of the display medium. For centuries, the two-dimensional plane of paper and chalkboard dictated the boundaries of instruction and conceptualization. Complex three-dimensional phenomena (whether the orbital mechanics of celestial bodies, the stress distribution in a bridge truss, or the electron geometry of a molecule) were flattened into static, often ambiguous 2D projections. The advent and subsequent democratization of 3D graphing calculators have precipitated a fundamental "spatial turn" in STEM disciplines. No longer confined to the Cartesian xy-plane, students, artists, and engineers can now navigate the z-axis with fluidity, transforming abstract algebraic expressions into tangible, manipulatable objects.

This report provides an exhaustive examination of the contemporary landscape of 3D graphing technology. It explores how tools like GeoGebra, Desmos, and Python-enabled handheld units from Texas Instruments and Casio have evolved from simple function plotters into sophisticated engines for physical simulation, algorithmic art, and architectural prototyping. As educational theorist John Dewey posited nearly a century ago, effective learning is experiential; 3D technology vindicates this view by making the invisible visible and the inaccessible accessible, allowing users to "experience" mathematical structures rather than merely calculate them. From the visualization of chaotic strange attractors to the fabrication of architectural gyroids via 3D printing, the modern 3D graphing calculator has become a pivotal instrument in bridging the gap between theoretical abstraction and physical reality.

Part I: The Pedagogical Revolution in STEM Education

The most pervasive application of 3D graphing calculators is the transformation of mathematics and science instruction. By enabling the real-time manipulation of three-dimensional objects, these tools have fundamentally altered the learning trajectory for subjects reliant on spatial reasoning.

Transforming Multivariable Calculus Instruction

Multivariable calculus has historically served as a "gatekeeper" course in engineering and mathematics curricula, largely due to the cognitive load required to visualize functions of two variables, z = f(x, y), without adequate visual aids. Traditional static diagrams fail to convey the dynamic nature of surfaces, leading to misconceptions about saddle points, gradients, and curvature.

Visualizing Scalar-Valued Functions and Surfaces

The core utility of 3D calculators in this domain is the immediate rendering of complex surfaces. Platforms like CalcPlot3D and GeoGebra 3D allow instructors to move beyond "hand-waving" and provide rigorous visual proofs.

- Surface Analysis: Students can plot quadric surfaces (ellipsoids, hyperboloids of one and two sheets, and elliptic paraboloids) and manipulate parameters dynamically. By rotating a graph of a hyperbolic paraboloid (z = y² - x²), students can intuitively grasp why the origin is a "saddle point" (a minimum in one direction and a maximum in another) without relying solely on the Second Derivatives Test.

- Level Curves and Contour Maps: A critical conceptual bridge in calculus is linking 3D topology with 2D topography. Tools like GeoGebra allow users to simultaneously display a 3D surface and its corresponding 2D contour map. By observing how the spacing of contour lines relates to the steepness of the 3D surface, students gain a tactile understanding of the gradient vector ∇f.

- Partial Derivatives: The abstract concept of a partial derivative is demystified through slicing. Users can insert a plane (e.g., y = 2) into the 3D view, visually cutting the surface. The intersection curve represents the single-variable function trace, and the slope of the tangent line to this curve visualizes the partial derivative ∂z/∂x. This interactive "slicing" technique bridges the gap between single-variable calculus and multivariable analysis.

Vector Calculus: Fields and Flows

The study of invisible forces (electromagnetic fields, fluid flows, and thermal gradients) relies heavily on vector calculus, a subject often obscured by notation.

- Vector Fields: Modern graphers can plot vector fields F(x, y, z) = <P, Q, R> where a vector is drawn at sample points in space. Students can adjust the density and scaling of these arrows to visualize phenomena like the "swirling" nature of a field with non-zero curl or the "outward flow" of a field with positive divergence.

- Line and Surface Integrals: Advanced scripts in GeoGebra allow for the visualization of line integrals. Students can define a path C through a vector field and watch as the calculator computes the dot product F · dr along the curve, physically representing the work done by a force field. Similarly, flux integrals can be visualized by rendering the surface S and the normal vectors n, helping students conceptualize the flow of fluid across a membrane.

- Gradient Fields: Visualizing ∇f as a field of vectors perpendicular to level surfaces provides a geometric intuition for optimization problems, showing the direction of steepest ascent instantly.

Geometry: Spatial Reasoning and Constructive Learning

In secondary education (K-12), the focus shifts from calculus to geometry and spatial reasoning. The ability to decompose 3D solids is crucial for understanding volume and surface area.

Nets and Polyhedra Unfolding

A standard curriculum requirement involves understanding the relationship between a 3D solid and its 2D "net" (the flat pattern that folds to create the shape). GeoGebra 3D features automated tools to "unfold" polyhedra. A student can construct a dodecahedron or icosahedron and, with a slider, slowly unfold it into the 2D plane. This dynamic animation helps students verify Euler’s formula (V - E + F = 2) and visualize surface area as a sum of 2D polygon areas, a cognitive step often missed with static paper models.

Cross-Sections and Conic Sections

Understanding conic sections (circles, ellipses, parabolas, and hyperbolas) as the intersections of a plane and a double cone is a foundational geometric concept often taught abstractly. 3D graphing calculators allow students to:

- Construct a double cone.

- Insert a movable plane.

- Manipulate the angle of the plane relative to the cone's axis.

As the student tilts the plane, they witness the intersection curve morph from a circle to an ellipse, then to a parabola (when parallel to the generator line), and finally to a hyperbola. This continuous transformation reinforces the unified nature of conic sections.

Physics and Chemistry Simulations

The integration of time parameters (t) and scripting capabilities has expanded the utility of graphing calculators into the physical sciences.

Kinematics and Dynamics

In physics, 3D calculators are used to model motion in space.

- Projectile Motion: Students can input parametric equations to model the path of a projectile in 3D, accounting for x, y, and z components of velocity. Lesson plans often involve simulating "throwing motions" where students adjust launch angles and initial velocities to hit a target, visually confirming the parabolic trajectory in real-time.

- Orbital Mechanics: Using parametric equations, students can simulate planetary orbits, verifying Kepler’s laws of planetary motion. Advanced users can model n-body problems, visualizing the complex gravitational dance of multiple celestial bodies.

- Electromagnetism: Visualizing electric and magnetic fields is notoriously difficult. Calculators can plot the electric field lines radiating from point charges or the magnetic field circling a current-carrying wire. By placing positive and negative charges in the 3D space, students can observe the superposition of fields, seeing how field lines bend and interact.

Molecular Modeling and Chemistry

While specialized molecular software exists, 3D graphing calculators provide an accessible platform for chemical visualization on devices students already own.

- VSEPR Theory: To understand molecular geometry, students use 3D points to represent atoms. By connecting them with vectors, they can model geometries predicted by Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) theory (linear, trigonal planar, tetrahedral, etc.). This helps in visualizing bond angles and understanding why methane (CH4) forms a tetrahedron rather than a flat square.

- Atomic Orbitals: The shapes of electron orbitals (s, p, d, f) are defined by spherical harmonics. 3D graphers can plot these probability isosurfaces, showing the characteristic "dumbbell" and "cloverleaf" shapes of p and d orbitals, helping students visualize the regions of high electron density.

- Stoichiometry Scripts: On programmable handhelds like the TI-Nspire CX II, students utilize Python scripts to perform stoichiometric calculations. Custom modules allow for mass-to-mole conversions, limiting reactant identification, and gas law calculations, with some apps providing step-by-step visual solutions.

Part II: The Artistic Frontier and Algorithmic Design

The intersection of rigorous mathematics and creative aesthetics has found a vibrant outlet in 3D graphing calculators. "Math art" has evolved from simple geometric patterns to complex, algorithmically generated scenes that rival professional 3D rendering software.

Desmos Art: Parametric Creativity

The global Desmos Art Contest serves as a showcase for the creative potential of graphing tools. Participants create intricate scenes using thousands of mathematical expressions.

- Techniques: Artists rarely use standard function plotting (z=f(x,y)) for these scenes. Instead, they rely heavily on parametric equations (x(t), y(t), z(t)) to draw lines, wires, and complex curves. A simple helix is defined as (cos t, sin t, t), but artists layer thousands of such curves to build "wireframe" structures of organic forms, architecture, and portraits.

- Animation: By defining variables linked to sliders (e.g., a for rotation angle), artists animate their creations. A static model of a Ferris wheel becomes a dynamic simulation by introducing a time variable t into the parametric equations of the wheel's spokes and cabins.

- Notable Examples: Winners of the contest have rendered everything from realistic portraits (using inequalities to shade regions) to complex architectural models like the "Lotus Temple" or intricate mechanical watches. "Tiger" by Charlene Uyen Dung Tran and "Perry the Parametric Pencil" by Courtney Winkowski are prime examples of this mathematical artistry.

Strange Attractors: The Beauty of Chaos

One of the most visually arresting uses of 3D graphing calculators is the visualization of strange attractors (fractal-like curves that arise from dynamical systems in chaos theory). These are systems of differential equations where the future behavior is highly sensitive to initial conditions.

The Aizawa Attractor: The Aizawa attractor is a favorite among math artists for its aesthetic elegance (a sphere-like structure with a tube penetrating its axis). To render this, users input a system of differential equations into a calculator capable of iterative solving (like GeoGebra or a Python-enabled TI-Nspire). The calculator traces the path of a particle over thousands of time steps, revealing the beautiful, chaotic structure.

The Lorenz and Other Systems: Calculators are also used to visualize the classic Lorenz Attractor (the "butterfly effect" model) and other systems like the Rossler, Chen-Lee, and Halvorsen attractors. Each system requires specific parameters to exhibit chaotic behavior. Visualizing these systems helps users appreciate the complexity of non-linear dynamics.

Ray Marching and Signed Distance Fields (SDFs)

Advanced users have pushed the capabilities of web-based calculators like Desmos to implement Ray Marching (a rendering technique used in modern computer graphics) directly within the graphing engine.

- The Concept: Instead of plotting explicit points, the user defines a Signed Distance Function (SDF). An SDF is a mathematical function that tells you, for any point (x,y,z) in space, the shortest distance to the surface of an object.

- Implementation: Users script a "camera" and "rays" using inequalities. The inequality checks if a ray originating from the camera intersects the SDF (i.e., distance ≤ 0). This allows Desmos to render smooth, lit, 3D blobs and fractals (like the Mandelbulb) that would be impossible to define with standard algebraic equations.

- Innovation: This technique effectively turns a graphing calculator into a programmable GPU shader, allowing for boolean operations (unions, intersections, subtractions) of complex shapes. For example, creating a "hollow" sphere by subtracting a smaller sphere SDF from a larger one.

Part III: Engineering, Architecture, and Professional Utility

Beyond the classroom and the art studio, 3D graphing calculators have found a niche in professional workflows. They serve as lightweight, accessible CAD tools for rapid prototyping, conceptual analysis, and structural design.

Parametric Graphic Statics in Civil Engineering

Civil engineers use 3D graphing tools for Parametric Graphic Statics, a method of analyzing structural forces using geometry rather than algebraic matrices.

- Interactive Force Diagrams: In tools like GeoGebra, an engineer can draw the Form Diagram (the geometry of a bridge or truss) and a corresponding Force Diagram (a vector polygon representing equilibrium).

- Dynamic Optimization: Because the geometry is parametric, dragging a node on the bridge instantly updates the force polygon. If a line in the force polygon becomes long, it visually indicates high stress in that member. This allows engineers to intuitively optimize structures (adjusting the arch of a bridge to minimize forces) before running computationally expensive Finite Element Analysis (FEA) simulations.

Architectural Geometry: Gyroids and TPMS

Modern architecture increasingly utilizes Triply Periodic Minimal Surfaces (TPMS) (surfaces that minimize area and repeat in three dimensions). These structures are lightweight, porous, and self-supporting, making them ideal for 3D-printed building facades and scaffolds.

The Gyroid: One of the most famous TPMS is the Gyroid, discovered by Alan Schoen. It separates space into two interpenetrating labyrinths. Architects use graphing calculators to visualize the Gyroid using its approximate trigonometric equation. Similarly, the Schwarz P ("Primitive") and D ("Diamond") surfaces are explored using implicit equations. By graphing these functions, designers can adjust periods and thresholds to control the wall thickness and pore size of the lattice structure before exporting the model for fabrication.

Rapid Prototyping: The Math-to-Matter Workflow

A growing trend is the direct fabrication of mathematical objects via 3D printing. This "Math-to-Matter" workflow allows abstract equations to become physical objects.

- Exporting Geometries: GeoGebra 3D includes a native "Export to STL" feature, specifically designed for this workflow. Desmos users utilize community-written scripts or bookmarklets to convert parametric surfaces into OBJ or STL files.

- Refinement: Users can import these STL files into slicer software (like Cura). Tutorials emphasize the need to adjust mesh resolution (or "precision" in the calculator) to ensure smooth prints, as low-resolution math graphs can result in faceted, blocky prints.

- Use Cases: This workflow is used to print educational aids (e.g., a physical model of a saddle point for a blind student), custom engineering parts (e.g., a gear with a specific non-standard tooth profile defined by an equation), or artistic sculptures.

Part IV: Hardware Ecosystem and Technical Capabilities

The utility of 3D graphing calculators is heavily dependent on the specific hardware and software ecosystem. The market is dominated by browser-based tools and programmable handheld units, each offering distinct advantages.

Browser-Based Powerhouses: Desmos and GeoGebra

Desmos 3D: Known for its speed and aesthetic rendering. It excels at handling implicit surfaces and inequalities, making it the preferred tool for "ray marching" experiments and art. It recently added features to handle OBJ parsing via lists, allowing it to render 3D point clouds imported from external data sources.

GeoGebra 3D: The "Swiss Army Knife" of math software. Its strength lies in its geometric construction tools (construct a plane through three points, bisect an angle) and its robust export features (STL for printing, AR for mobile). It is deeply integrated into curriculum resources like Illustrative Mathematics.

Handheld Giants: TI-Nspire and Casio fx-CG50

The integration of Python into handheld calculators has revolutionized their capability, allowing them to serve as miniature computers.

- TI-Nspire CX II: This device features a dedicated Python environment. It includes specific modules like ti_draw and ti_image for pixel-level graphics control, allowing users to script custom 3D rendering engines if the native grapher is insufficient. The programmability has led to the development of sophisticated chemistry suites that handle stoichiometry, gas laws, and periodic table data visualization.

- Casio fx-CG50 (PRIZM): Known for its "exam mode" and durability, it also supports MicroPython. Unlike the TI, which often relies on Python for advanced 3D, the Casio has a robust native 3D graphing app that supports Sphere, Cylinder, Plane, and Line templates directly from the menu. It allows for zooming, rotating, and cross-sectioning natively.

Data Import and Interoperability

Advanced users leverage the ability to import external data into these systems. Researchers can import CSV data representing 3D coordinates (e.g., from a LiDAR scan or a physics experiment) into Desmos or GeoGebra to visualize the data in 3D space. Scripts have been written to parse standard OBJ 3D model files into Desmos lists. This allows the calculator to render complex 3D meshes (like a scan of a human face or a terrain map) by mathematically plotting the triangles defined in the file.

Part V: Augmented Reality (AR) - Merging Worlds

The most futuristic application of 3D graphing technology is Augmented Reality (AR), primarily spearheaded by the GeoGebra 3D mobile app. This feature transforms the calculator from a screen-bound tool into an immersive spatial computer.

Mechanics and Interaction

The app uses the phone's camera and accelerometer to detect flat surfaces (floors, tables). The user taps to place the origin (0,0,0) on the physical surface. Once an object is placed, it is "locked" in physical space. A student can graph a surface, such as a hyperbolic paraboloid, and physically walk around it to see the back, or walk through it to inspect the curvature from the inside. This kinesthetic interaction provides a sense of scale and structure that screens cannot convey.

The "Math Scavenger Hunt"

Educators have developed innovative "scavenger hunts" that utilize AR to connect math to the real world. Students are given a checklist of mathematical shapes (cylinder, parabola, acute angle) and must find a real-world object that matches the shape (e.g., a trash can for a cylinder, a water fountain arc for a parabola). Using the AR app, they overlay the mathematical primitive onto the physical object to verify their model.

Real-World Modeling Challenges

Specific modeling challenges push students to derive equations for complex real objects. In the "Toblerone" Challenge, students must model the triangular prism of a Toblerone bar. They measure the real bar, derive the planes and inequalities to define the prism, and use AR to project the virtual model onto the physical candy. Similar challenges involve modeling truncated cones and solids of revolution, like popcorn bowls and lampshades.

Comparative Analysis of Technical Capabilities

| Feature Category | GeoGebra 3D | Desmos 3D | TI-Nspire CX II (Handheld) | Casio fx-CG50 (Handheld) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Strength | Geometric Construction, AR, Nets | Speed, Rendering Aesthetics, SDFs | Programmability (Python), CAS | Durability, Exam Compliance, Native 3D |

| Augmented Reality | Native (Mobile App) with Surface Detection | No | No | No |

| 3D Printing Export | Direct STL Export (Native) | Via Community Scripts (OBJ/STL) | No | No |

| Scripting Language | GeoGebraScript, JavaScript | Simulation Actions, LaTeX | Python (MicroPython), TI-Basic | Python (MicroPython) |

| Best Use Case | Geometry Education, K-12, AR | Calculus, Art, Ray Marching | Engineering, Physics Simulations | Rapid Calculations, Standardized Testing |

| Advanced Visualization | Unfolding Polyhedra, Cross-sections | Implicit Surfaces, Inequalities | Custom Graphics Modules (ti_draw) | Pre-built Templates (Sphere, Cylinder) |

Detailed Case Study: The Aizawa Attractor

To illustrate the depth of capability in modern programmable calculators, the following table details the implementation of the Aizawa Attractor, a chaotic system often used to demonstrate the graphical prowess of these devices.

| Aizawa Attractor Implementation | |

|---|---|

| Differential Equations |

dx/dt = (z - b)x - dy dy/dt = dx + (z - b)y dz/dt = c + az - z³/3 - (x² + y²)(1 + ez) + fzx³ |

| Parameters | a=0.95, b=0.7, c=0.6, d=3.5, e=0.25, f=0.1 |

| Execution Method | Iterative loop (Python script on TI-Nspire or GeoGebra Sequence) |

| Time Step (dt) | 0.01 |

| Iterations | 10,000+ |

| Visual Result | A tube-like volumetric shape verifying chaotic nature and sensitivity to initial conditions. |

Conclusion

The 3D graphing calculator has transcended its origins as a mere computational convenience to become a fundamental infrastructure for spatial thinking. It has evolved into a multidimensional workspace that serves three distinct masters:

- The Educator: Providing a tactile, visual, and immersive bridge to complex concepts in calculus, physics, and chemistry.

- The Artist: Offering a canvas of infinite precision where equations become aesthetic objects through parametric design and chaotic dynamics.

- The Professional: Delivering a lightweight, programmable, and export-capable tool for structural analysis, architectural geometry, and rapid prototyping.

From the visualization of the Aizawa attractor to the parametric optimization of bridge trusses, the modern 3D graphing calculator demonstrates that the boundary between "learning math" and "doing math" is becoming increasingly porous. As hardware capabilities expand to include native Python scripting and seamless AR integration, these tools will likely become the primary interface through which the next generation interacts with the third dimension.

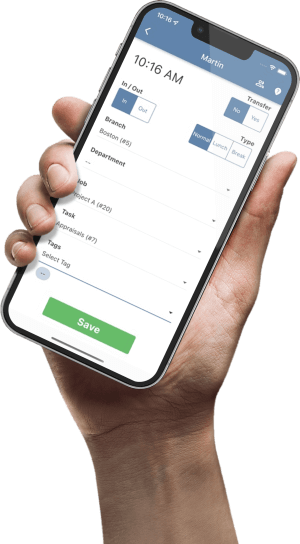

Equip Your Institute with the Best Tools

Discover how TimeTrex helps educational institutes manage their workforce efficiently, leaving more time for innovation in the classroom.

Explore Solutions for Educational InstitutesDisclaimer: The content provided on this webpage is for informational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice. While we strive to ensure the accuracy and timeliness of the information presented here, the details may change over time or vary in different jurisdictions. Therefore, we do not guarantee the completeness, reliability, or absolute accuracy of this information. The information on this page should not be used as a basis for making legal, financial, or any other key decisions. We strongly advise consulting with a qualified professional or expert in the relevant field for specific advice, guidance, or services. By using this webpage, you acknowledge that the information is offered “as is” and that we are not liable for any errors, omissions, or inaccuracies in the content, nor for any actions taken based on the information provided. We shall not be held liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, consequential, or punitive damages arising out of your access to, use of, or reliance on any content on this page.

Trusted By

Trusted by 3.2M+ Employees: 21 Years of Service Across Startups to Fortune 500 Enterprises

Join our ever-growing community of satisfied customers today and experience the unparalleled benefits of TimeTrex.

Strength In Numbers

Join The Companies Already Benefiting From TimeTrex

Time To Clock-In

Start your 30-day free trial!

Experience the Ultimate Workforce Solution and Revolutionize Your Business Today

- Eliminate Errors

- Simple & Easy To Use

- Real-time Reporting

Saving businesses time and money through better workforce management since 2003.

Copyright © 2025 TimeTrex. All Rights Reserved.