Free FLSA Time Clock Rounding Calculator

Time Clock Rounding Calculator

Calculation Results

Disclaimer: The Time Clock Rounding Calculator is provided for general informational and illustrative purposes only and is not intended as legal, payroll, tax, or compliance advice. While the calculator is designed to reflect common interpretations of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) 15-minute (7-minute split) rounding guidance, actual compliance requirements may vary based on federal, state, provincial, local, union, or contractual regulations. Users are solely responsible for verifying the accuracy of inputs, calculations, and results before relying on them for payroll processing or employment decisions. The creators and publishers of this tool assume no liability for errors, omissions, miscalculations, system limitations, or any direct or indirect damages arising from its use. Employers should consult qualified legal counsel or payroll professionals to ensure full compliance with all applicable labor laws and wage regulations.

Found our Free FLSA Time Clock Rounding Calculator useful? Bookmark and share it.

FLSA Time Clock Rounding: 2026

In the modern landscape of workforce management, FLSA time clock rounding remains one of the most contentious issues facing HR departments and payroll administrators. While federal regulations have historically permitted rounding to the nearest quarter-hour, recent shifts in state legislation and the technological capabilities of modern timekeeping systems are eroding the legal defenses for this practice. This article provides a deep dive into the mechanics of time rounding, the "7-minute rule," and why the "administrative difficulty" defense is crumbling in courts across California, Oregon, and Washington.

TL;DR

Time clock rounding is rapidly becoming a legal liability. While 29 C.F.R. § 785.48(b) technically permits neutral rounding, technological advancements in cloud-based payroll systems have rendered the "administrative difficulty" defense obsolete. Courts in California, Oregon, and Washington are moving toward a "pay-to-the-minute" standard. To avoid class-action lawsuits and wage theft claims, the safest strategy for 2026 is to eliminate rounding entirely and utilize exact punch times.

Article Index

- Part I: The Historical and Legal Foundations of Timekeeping

- Part II: The Mechanics of Rounding Intervals

- Part III: The Erosion of the Neutrality Defense (California)

- Part IV: The National Landscape – State Divergence

- Part V: Forensic Auditing and Statistical Methodology

- Part VI: The Technology Paradox and Modern Solutions

- Part VII: Psychological and Economic Implications

- Part VIII: Strategic Recommendations for 2026 and Beyond

Part I: The Historical and Legal Foundations of Timekeeping

1.1 The Industrial Origins of Time Rounding

The practice of time clock rounding is an artifact of the industrial revolution, born from the mechanical limitations of early timekeeping devices and the administrative burden of manual payroll calculation. In the mid-20th century, the standard mechanism for tracking employee attendance was the analog punch clock. Workers would insert a heavy cardstock timecard into a machine that would physically stamp the time, often with a margin of error due to the calibration of the clock or the speed of the line of workers waiting to punch in.

When the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) was enacted in 1938, the Department of Labor (DOL) recognized that requiring employers to pay for every precise minute recorded on these analog devices was impractical. A payroll clerk in a factory of 5,000 workers, calculating wages by hand using timestamps that might be smeared or overlapping, faced a herculean task if required to account for 8 hours and 3 minutes versus 7 hours and 58 minutes. To facilitate the smooth administration of payroll, the DOL codified the concept of "rounding" under 29 C.F.R. § 785.48(b).

This regulation explicitly acknowledged that "minor differences between the clock records and actual hours worked cannot ordinarily be avoided." It permitted employers to round start and stop times to the nearest five minutes, one-tenth of an hour (six minutes), or quarter of an hour (fifteen minutes). The foundational premise was "administrative difficulty" - the idea that the cost and effort of precise calculation outweighed the value of the trifling amounts of time lost or gained. However, this concession came with a critical caveat: the arrangement must average out over time so that employees are fully compensated for all time actually worked.

1.2 The Federal Regulatory Framework: 29 C.F.R. § 785.48(b)

The core legal text governing rounding is brief but dense with implication. 29 C.F.R. § 785.48(b) states that rounding practices will be accepted for enforcement purposes "provided that it is used in such a manner that it will not result, over a period of time, in failure to compensate the employees properly for all the time they have actually worked."

This provision establishes the "neutrality" requirement. A rounding policy cannot be designed to solely benefit the employer. For instance, a policy that always rounds down (docking time for late arrivals but not crediting time for early arrivals) is facially unlawful. Similarly, a policy that rounds in 15-minute increments must theoretically result in a "zero-sum" outcome where the minutes gained by the employee in some instances offset the minutes lost in others.

1.3 The Intersection with the De Minimis Doctrine

Parallel to the rounding regulation is the judicial doctrine of de minimis non curat lex ("the law does not concern itself with trifles"). Established by the U.S. Supreme Court in Anderson v. Mt. Clemens Pottery Co. (1946), this doctrine allows employers to disregard "insubstantial and insignificant" periods of time beyond scheduled working hours that are administratively difficult to record.

While rounding and de minimis are distinct legal concepts, they are often conflated in defense strategies. Rounding is a systematic mathematical adjustment of recorded time, whereas de minimis is a defense for unrecorded time (e.g., the 30 seconds it takes to power down a computer). However, as discussed in later sections, this defense is crumbling. If a time clock records a punch at 8:04 AM, that time is not "unrecorded" - it is captured data. Therefore, the "difficulty to record" prong of the de minimis test is often unsatisfied in modern rounding cases.

Part II: The Mechanics of Rounding Intervals

To understand the compliance risks, one must first master the arithmetic of permissible rounding. The FLSA allows for three primary increments: the 15-minute rule, the 6-minute rule, and the 5-minute rule.

2.1 The 15-Minute Rule (The "7-Minute Rule")

The most prevalent and most litigated form of rounding is to the nearest quarter-hour. This is often colloquially referred to as the "7-Minute Rule" because the breakpoint for rounding up or down occurs at the 7-minute mark past the quarter-hour.

- 0 to 7 Minutes: Round down to the previous quarter-hour.

- 8 to 14 Minutes: Round up to the next quarter-hour.

This creates a distinct "zone of risk" for employers. If employees consistently clock in at 8:08 AM (rounded to 8:15 AM) and clock out at 5:07 PM (rounded to 5:00 PM), the employee loses 22 minutes of pay in a single day despite working nearly a full shift.

| Actual Punch Time | Minutes Past Hour | Action | Rounded Time | Employee Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 08:00 | 00 | None | 08:00 | Neutral |

| 08:04 | 04 | Round Down | 08:00 | Gain 4 mins (if punch out) |

| 08:07 | 07 | Round Down | 08:00 | Gain 7 mins / Loss 7 mins |

| 08:08 | 08 | Round Up | 08:15 | Loss 7 mins / Gain 7 mins |

| 08:14 | 14 | Round Up | 08:15 | Loss 1 min / Gain 1 min |

| 08:22 | 22 | Round Down | 08:15 | Gain 7 mins / Loss 7 mins |

2.2 The 6-Minute Rule (1/10th of an Hour)

The 6-minute rule is favored by industries that bill clients in tenths of an hour, such as legal firms, engineering consultancies, and government contractors. It simplifies payroll calculation by converting minutes into decimal hours immediately.

| Minute Segment | Decimal Equivalent | Rounded Minute |

|---|---|---|

| :57 - :02 | .0 | :00 |

| :03 - :08 | .1 | :06 |

| :09 - :14 | .2 | :12 |

| :15 - :20 | .3 | :18 |

| :21 - :26 | .4 | :24 |

| :27 - :32 | .5 | :30 |

| :33 - :38 | .6 | :36 |

| :39 - :44 | .7 | :42 |

| :45 - :50 | .8 | :48 |

| :51 - :56 | .9 | :54 |

2.3 The 5-Minute Rule (1/12th of an Hour)

The 5-minute rule is less common but still permissible. It offers a tighter variance than the quarter-hour method but lacks the decimal convenience of the 1/10th hour method. This method is often found in legacy manufacturing environments where time clocks were geared to 5-minute intervals. Like the 6-minute rule, it minimizes the "delta" between paid time and worked time.

2.4 The Problem of Asymmetric Rounding

While the tables above describe neutral rounding, some employers attempt to manipulate these rules. A common violation is "docking" rounding, where late arrivals are rounded forward (docking pay) but late departures are rounded backward (denying overtime). Such practices are explicitly illegal under federal regulation because they do not average out; they systematically favor the employer.

Part III: The Erosion of the Neutrality Defense (California Jurisprudence)

Nowhere is the battle over time rounding more intense than in California. As a bellwether for labor law, California's judicial shift often predicts national trends. The state has moved from a position of adopting federal standards to one of skepticism, and finally, to near-total prohibition in the context of modern technology.

3.1 The See's Candy Standard (2012)

For a decade, the controlling authority in California was See's Candy Shops, Inc. v. Superior Court. In this case, the California Court of Appeal adopted the federal standard, ruling that a rounding policy is lawful if it is "neutral on its face and as applied." The court accepted the premise that over a period of time, the "minuses" and "pluses" would cancel each other out.

3.2 The Donohue Pivot: Meal Breaks (2021)

The first crack in the See's Candy foundation appeared with Donohue v. AMN Services, LLC. The California Supreme Court ruled unanimously that employers cannot round time punches for meal periods. The court reasoned that rounding is incompatible with the strict requirement for a 30-minute meal period. Implication: The Donohue decision forced California employers to configure their timekeeping systems to track meal breaks to the exact minute.

3.3 Camp v. Home Depot: The Existential Threat (2022-2026)

The definitive challenge to rounding arrived with Camp v. Home Depot U.S.A., Inc. The California Court of Appeal reversed a trial court's summary judgment in favor of Home Depot. The court distinguished See's Candy by focusing on the technological capability of the employer.

The court noted that Home Depot "captured the exact minute" of the punch and then executed an algorithmic process to round it. Because the exact data existed and could be used for payment without administrative burden, the court questioned whether any rounding that resulted in underpayment for an individual could be lawful. As of early 2026, the case remains pending with the California Supreme Court, with the legal community anticipating a ruling that will likely ban rounding entirely for digital timekeeping.

Part IV: The National Landscape – State Divergence

While California leads the charge, other states have developed distinct jurisprudential approaches to rounding, creating a patchwork of compliance requirements for multi-state employers.

4.1 Oregon: Strict Prohibition

Oregon has adopted perhaps the most rigid stance against rounding in the nation. The Oregon Bureau of Labor and Industries (BOLI) and federal district courts have interpreted Oregon's wage statutes as prohibiting the practice entirely if it results in any failure to pay for all hours worked. Key Precedent: Eisele v. Home Depot U.S.A., Inc., where the court bluntly stated, "Oregon does not permit rounding."

4.2 Washington: The "Providence" Warning

Washington State technically permits rounding under Administrative Policy ES.D.1, provided the practice is neutral and averages out. However, a massive class-action verdict against Providence Health & Services ($9.3 million) highlighted the danger. The verdict emphasized that the burden of proof for "averaging out" is high.

4.3 Pennsylvania: The Heimbach Effect

In Heimbach v. Amazon.com, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court held that the Pennsylvania Minimum Wage Act does not contain a de minimis exception. Every minute an employee is required to be on the premises is compensable. This effectively serves as a ban on rounding that results in net underpayment.

| Jurisdiction | Rounding Status | Key Legal Risk | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| California | Critical Risk | Camp (Pending), Donohue | Eliminate Rounding. Pay to the minute. |

| Oregon | Prohibited | Eisele, BOLI Guidance | Eliminate Rounding. Pay to the minute. |

| Washington | High Risk | Providence Verdict | Pay to the minute or audit monthly. |

| Pennsylvania | High Risk | Heimbach (No de minimis) | Pay to the minute to ensure "all hours" paid. |

| New York | Moderate Risk | NY Labor Law Art. 19 | Neutrality audits required; watch OT impact. |

| Federal (FLSA) | Moderate Risk | 29 CFR 785.48(b) | Permitted if neutral; tech feasibility arguments rising. |

Part V: Forensic Auditing and Statistical Methodology

For employers who continue to utilize time rounding, the only defense against class-action litigation is a robust, ongoing forensic audit program. This section details the statistical methodologies used by plaintiff attorneys and defense experts to prove or disprove "neutrality."

5.1 The Data Set: Actual vs. Rounded

A valid audit requires two sets of data: Punch Time (Raw) and Paid Time (Rounded). If an employer fails to preserve the Raw Time, they may face an "adverse inference" instruction in court.

5.2 The "Delta" Analysis

The fundamental metric in a rounding audit is the Delta.

Positive Delta: The employee was paid for more time than they worked.

Negative Delta: The employee was paid for less time than they worked.

Zero Delta: The rounding had no effect.

Part VI: The Technology Paradox and Modern Solutions

The most profound shift in the rounding debate is technological. The legal justification for rounding - administrative difficulty - has been rendered obsolete by the very tools used to track time.

6.1 The Cloud Computing Reality

Modern Human Capital Management (HCM) platforms calculate time to the millisecond. The Paradox: To round time in these systems, the software must first capture the exact time, then run a script to alter that time to a rounded figure. Courts view this extra step as an intentional choice to deprive employees of exact pay, rather than a necessity.

6.2 Biometric Friction and "Boot-Up" Time

While digital clocks are precise, the physical act of clocking in has new friction points. The proper solution for line-waiting is to place more clocks or pay for the waiting time, not to use a mathematical rounding formula that might exacerbate the loss.

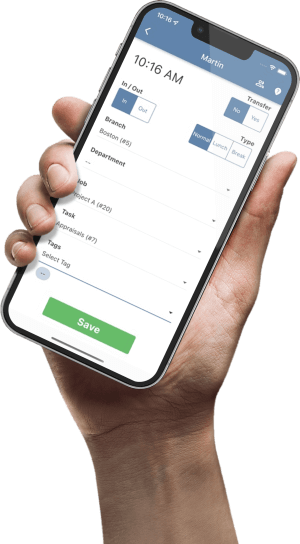

Modernize Your Timekeeping

Eliminate the risks of rounding with precision tracking. Ensure compliance and accuracy with the TimeTrex Mobile Time Clock app.

Get the AppPart VII: Psychological and Economic Implications

Beyond the legal mechanics, rounding policies have significant psychological and economic effects on the workforce. Employees today have access to their own digital records. They can see on their mobile app that they punched in at 7:58 and out at 5:02, yet their pay stub shows 8:00 to 5:00. Even if this is legal, the perception is that the company stole 4 minutes. This perceived "nickel and diming" erodes trust and is often the trigger for wage-and-hour lawsuits.

Part VIII: Strategic Recommendations for 2026 and Beyond

Given the hostile judicial climate in California, Oregon, and Washington, and the eroding "administrative difficulty" defense federally, employers must adopt a defensive posture.

8.1 The "Gold Standard": Pay to the Minute

The only risk-free strategy in 2026 is to eliminate rounding entirely. Configure timekeeping systems to record and pay based on exact punch times. This immunizes the organization against rounding lawsuits and improves employee trust.

8.2 Strategy for "Must-Round" Employers

For employers who cannot eliminate rounding, the following safeguards are non-negotiable:

- Quarterly Audits: Perform the "Delta" analysis quarterly.

- True-Up Payments: If the audit shows a net negative for any employee, pay the difference immediately.

- Meal Break Isolation: Disable rounding for all meal punches, regardless of state.

- State Segmentation: Apply rounding only in permissive states and disable it for employees in "Red Zone" states (CA, OR, WA, PA).

Appendix: Summary of Rounding Rules and Limits

| Rounding Interval | Breakpoint (Round Up) | Max Loss per Punch | Max Gain per Punch | Risk Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 Minutes | 8 minutes | 7 minutes | 7 minutes | High (Large variance) |

| 6 Minutes (1/10) | 4 minutes | 3 minutes | 3 minutes | Medium |

| 5 Minutes (1/12) | 3 minutes | 2 minutes | 2 minutes | Low (Tightest variance) |

| Exact Time | N/A | 0 minutes | 0 minutes | Zero (Best Practice) |

Disclaimer: The content provided on this webpage is for informational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice. While we strive to ensure the accuracy and timeliness of the information presented here, the details may change over time or vary in different jurisdictions. Therefore, we do not guarantee the completeness, reliability, or absolute accuracy of this information. The information on this page should not be used as a basis for making legal, financial, or any other key decisions. We strongly advise consulting with a qualified professional or expert in the relevant field for specific advice, guidance, or services. By using this webpage, you acknowledge that the information is offered “as is” and that we are not liable for any errors, omissions, or inaccuracies in the content, nor for any actions taken based on the information provided. We shall not be held liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, consequential, or punitive damages arising out of your access to, use of, or reliance on any content on this page.

Trusted By

Trusted by 3.2M+ Employees: 21 Years of Service Across Startups to Fortune 500 Enterprises

Join our ever-growing community of satisfied customers today and experience the unparalleled benefits of TimeTrex.

Strength In Numbers

Join The Companies Already Benefiting From TimeTrex

Time To Clock-In

Start your 30-day free trial!

Experience the Ultimate Workforce Solution and Revolutionize Your Business Today

- Eliminate Errors

- Simple & Easy To Use

- Real-time Reporting

Saving businesses time and money through better workforce management since 2003.

Copyright © 2025 TimeTrex. All Rights Reserved.